every3point65 - Toronto

mkg 127, Toronto

February 15 - March 15, 2014

MKG127 is pleased to present every3point65, an exhibition of new work by K.Nicol, produced with the support of the City of Toronto through the Toronto Arts Council

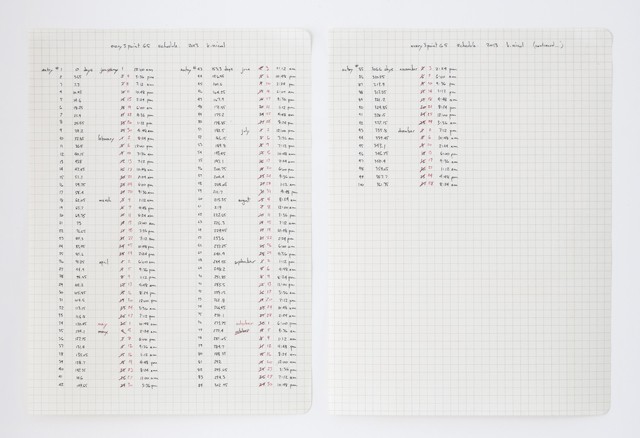

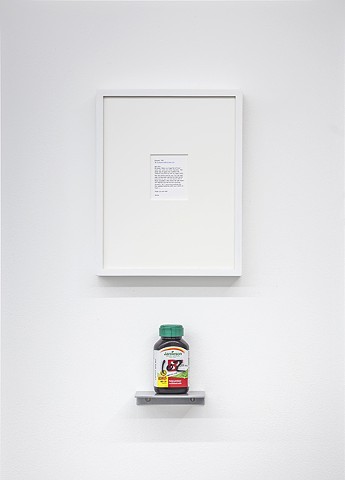

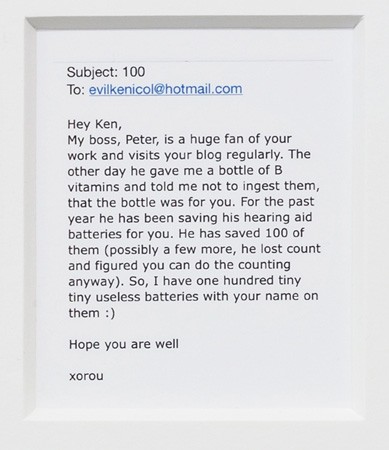

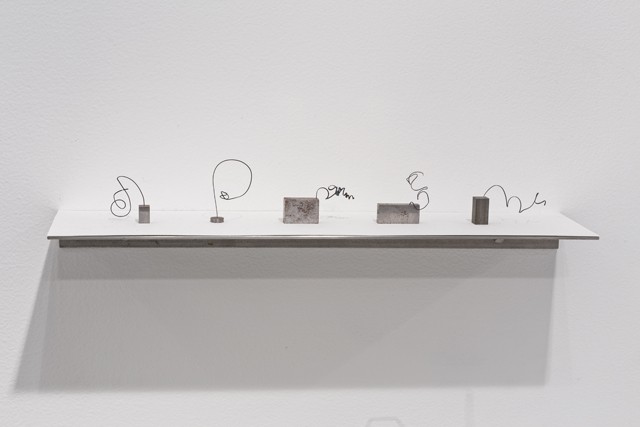

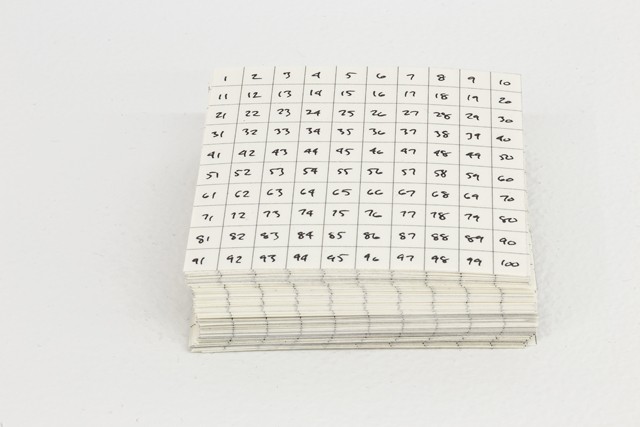

K. Nicol's third solo exhibition at MKG127 derives its title from a blog, every3point65 that he started on January 1st 2013 and updated every 3.65 days resulting in exactly one hundred entries in a year. An offshoot of his last solo exhibition at MKG127, hundreds of things vol.1, the blog reports directly from Nicol's studio or as he likes to call it "Ken's world." The exhibition is a physical realization of the blog with each work in the show corresponding to a numbered blog entry.

Reviews

Ken Nicol's every3point65 at MKG gallery, The Star: Visual Arts, Murray Whyte, February 20, 2014.

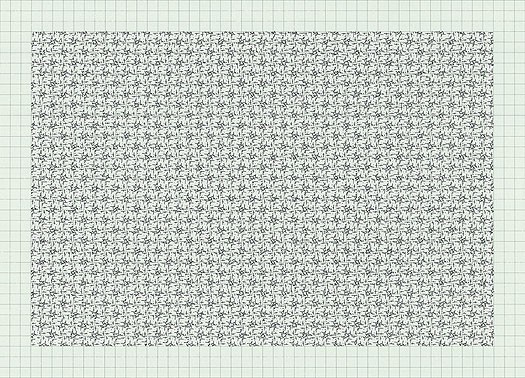

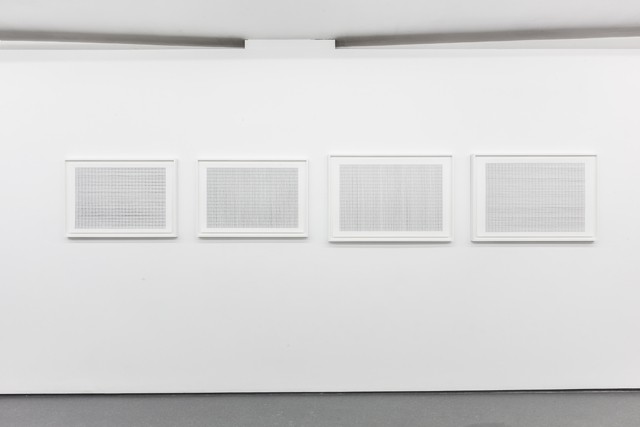

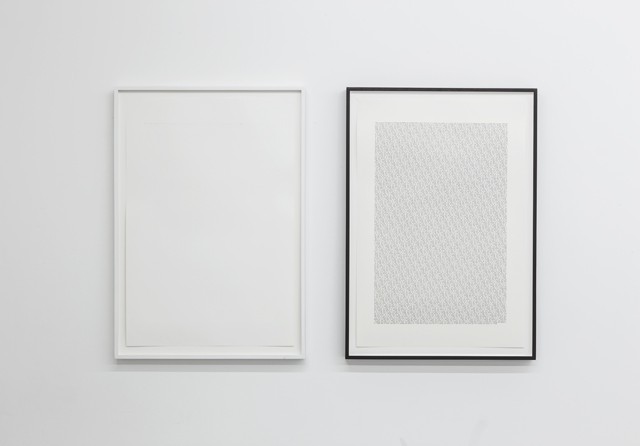

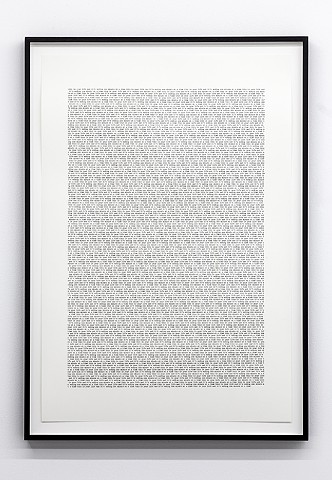

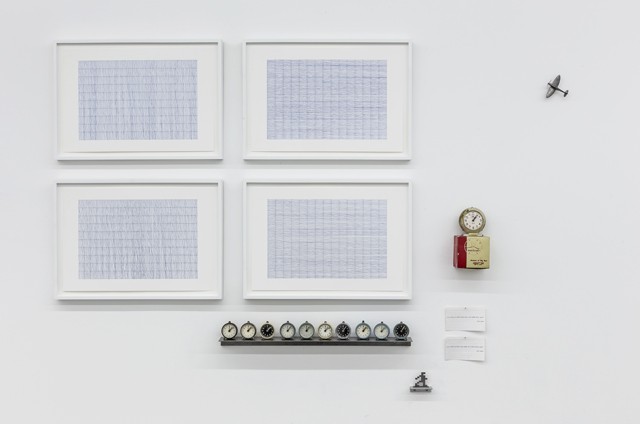

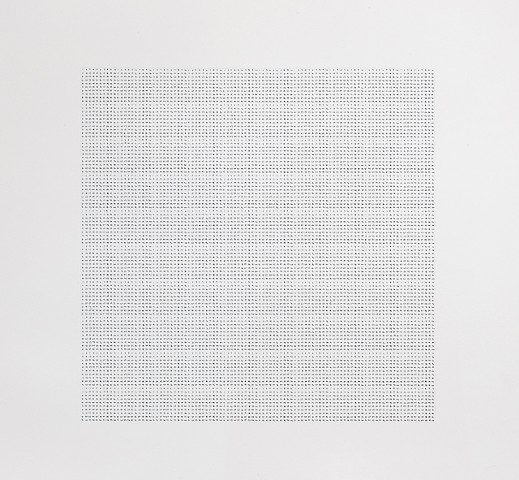

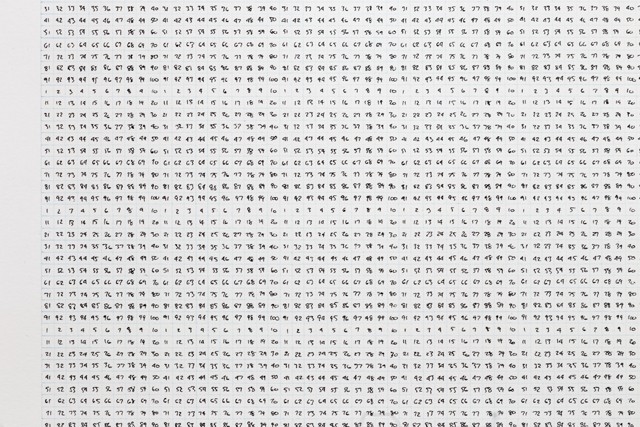

"Somewhere near the back of MKG127, a Dundas St. W. gallery, a large, typewritten grid in blocky courier font repeats, over and over, something you already know: “this is your life and it’s ending one minute at a time.” If you were to count, and you can trust me on this, you’d find it typed out exactly 480 times: the precise number of minutes in an eight-hour work day.

If you don’t find this funny — at least in a bleak, depressive, looming-shadow-of-death kind of way — then maybe the obsessive, darkly hilarious world of Ken Nicol isn’t for you. But that would be a shame, because you’d be missing out on an artist who has emerged in recent years here as an insider’s favourite; an artist’s artist, you might even say, however much the term would make him cringe.

Nicol’s new show, every3point65 (more on that later) opened this week, and puts on nice display both his bewildering skill and engagingly fatalistic world view. An expert machinist, Nicol for years made his way using his dizzyingly precise fussiness to realize work for people whose ideas were beyond their ability to make it themselves. Since he said goodbye to all that a few years back, Nicol has come into his own, exposing, by careful degrees, the deep rabbit hole of his workaday life that provides endless possibilities for his work.

Don’t take my word for it. Nicol’s an analog guy, in case the typewriter wasn’t enough of a clue, but technology has recently crept into his rituals as a useful tool, prompting him to start a blog (go, but be warned: it’s completely absorbing and dangerously addictive.)

The blog’s title is also the title of the show here, every3point65, which itself is an extension of the Nicol project to order his world into manageable constituent parts: the blog, he decided, would display exactly 100 posts a year, meaning a new entry — like clockwork, naturally — every 3.65 days.

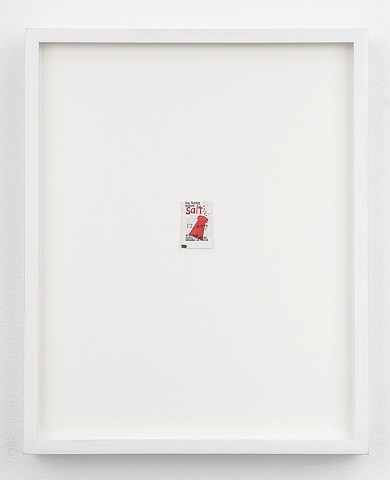

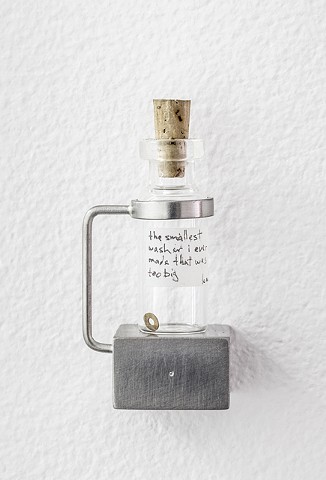

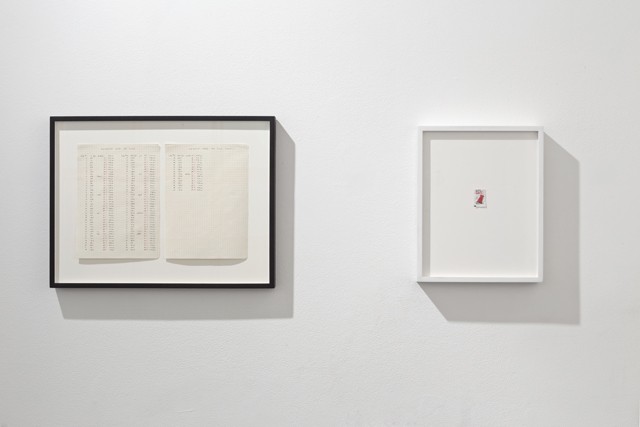

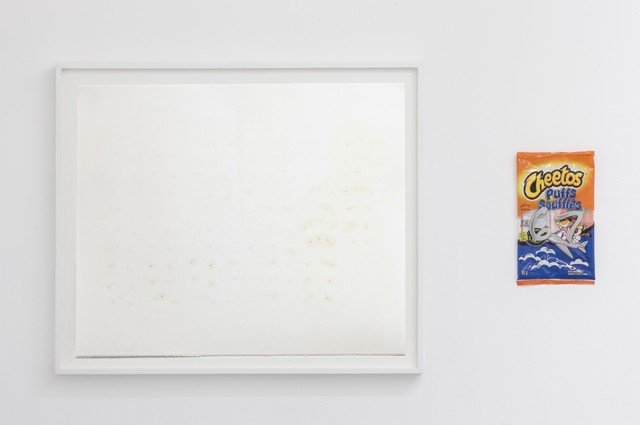

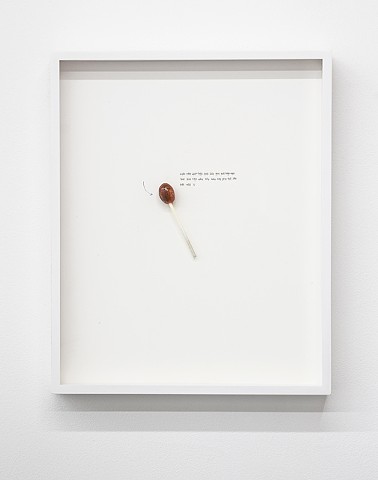

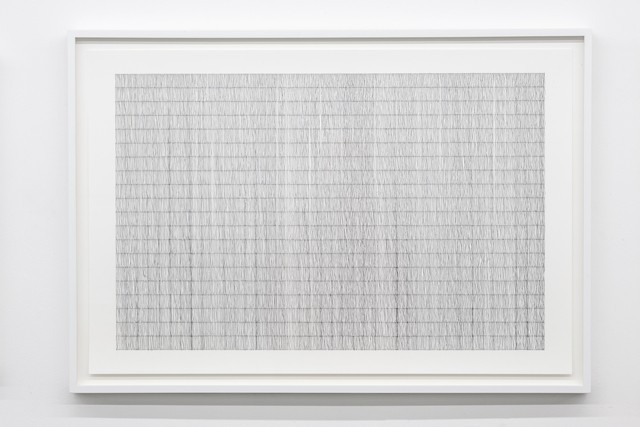

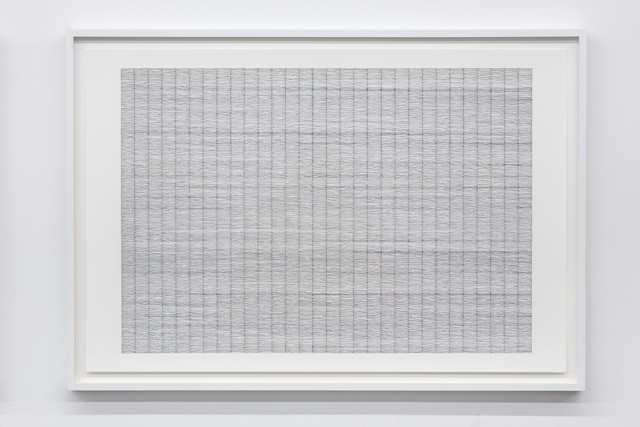

You get the idea: Nicol’s an old-school conceptualist, fusing an absurdist glee with quotidien ritual and everyday things: counting this, ordering that and trying, with sisyphusian hilarity, to impose structure on the persistent entropy of daily life. This is a quietly joyful thing to behold: Answering an age-old question, a Tootsie Pop, mounted with the number of licks to the centre (112); or a standard salt packet with a small tear in the corner and a number printed on it in ballpoint: 12,097 and yes, he counted them all.

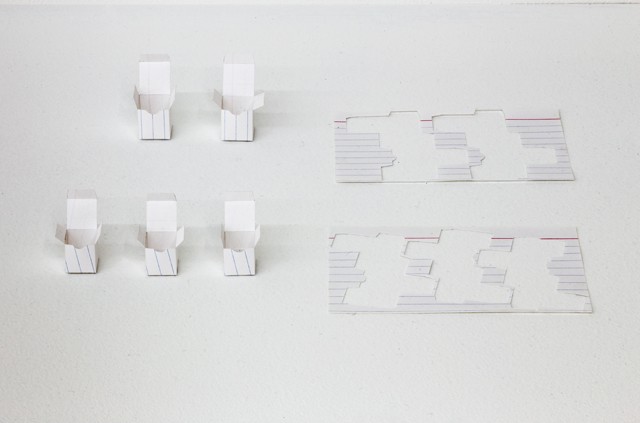

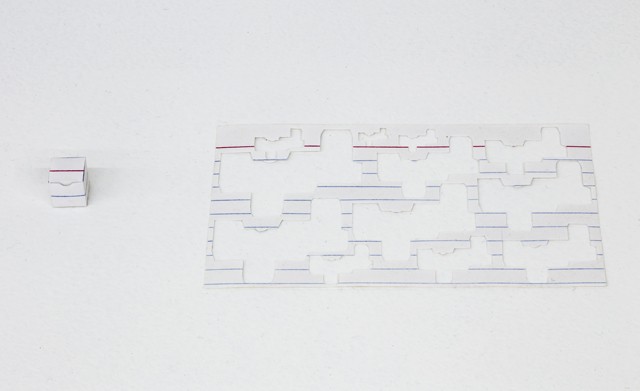

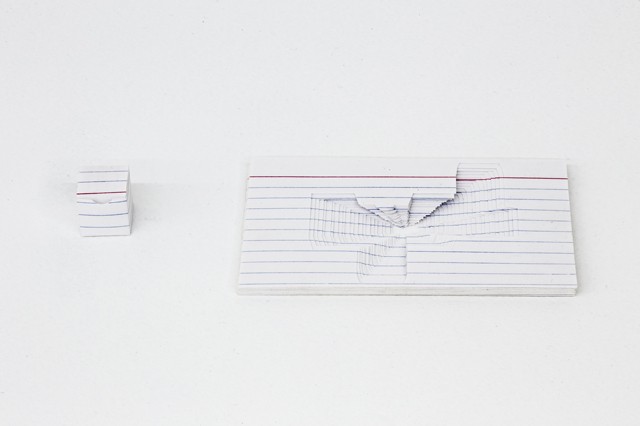

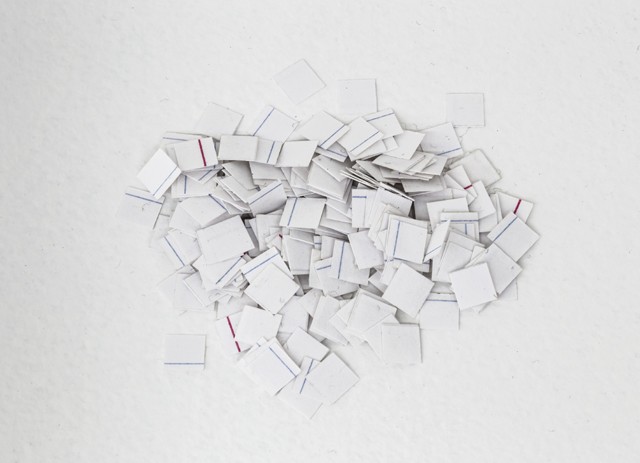

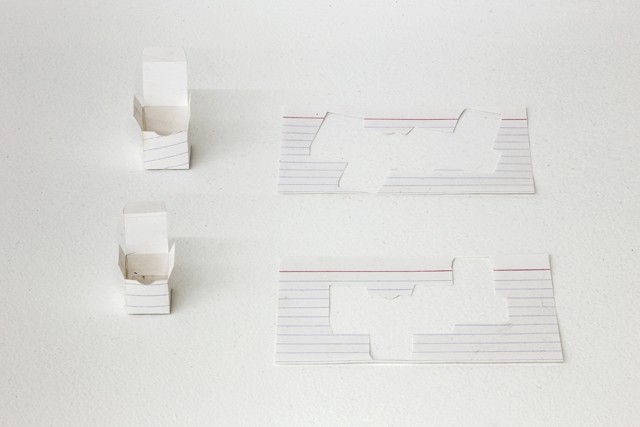

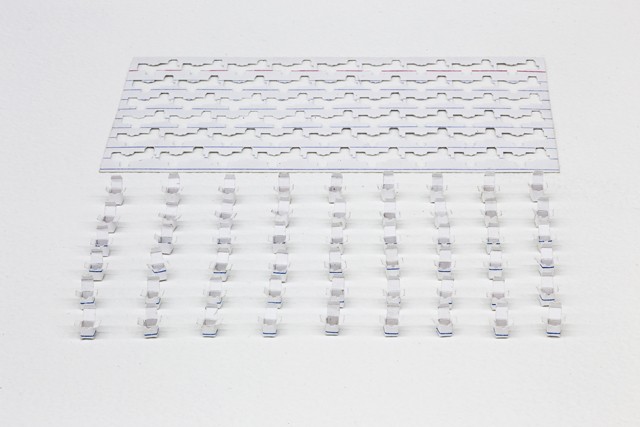

Or take Project Index Card: in a corner of the gallery, Nicol has taken his nominal subject, humble and blue-lined, and bent it to his compulsive will. Here, 54 tiny paper boxes, the maximum he could make, he calculated, from a single card, also here displayed with the tiny, precise cut-outs.

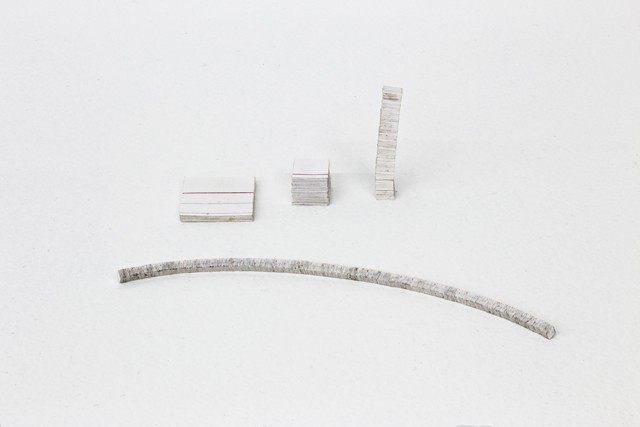

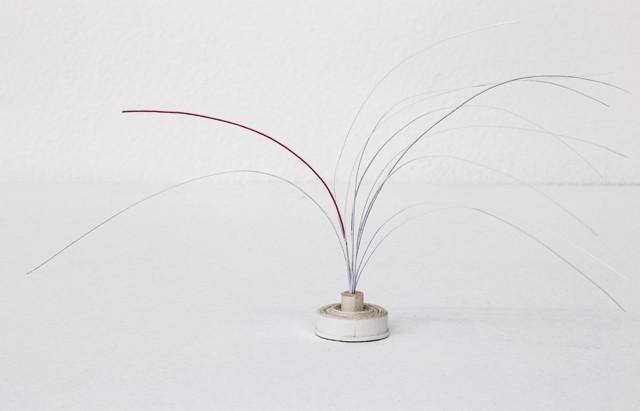

Over there, nesting boxes — each smaller than the next, packed one inside the other — maxed out again from a single card. Nearby, an uncharacteristic flourish he calls fountain: each of the coloured lines is precisely carved out and the remaining, colourless strips are wrapped tight around, like a flouncy bouquet.

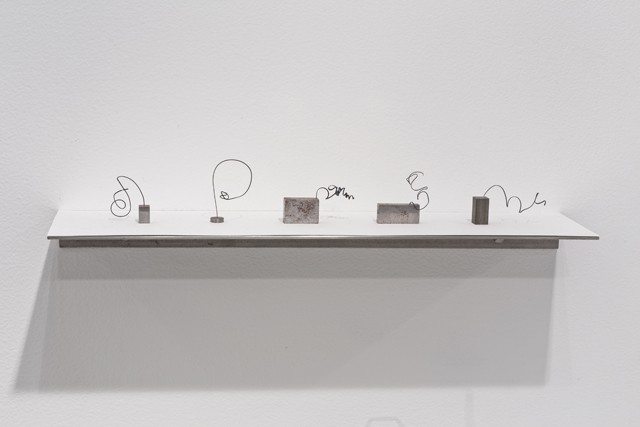

Nicol’s influences are writ large here. There are echoes of minimalist giant Carl Andre: 32 cubes, 32 ways is what it says, with the steel cubes starting at an inch and sizing down, 1/32 of an inch at a time, until the final one is but a speck (Nicol is rearranging them 32 times, of course, over the run of the show).

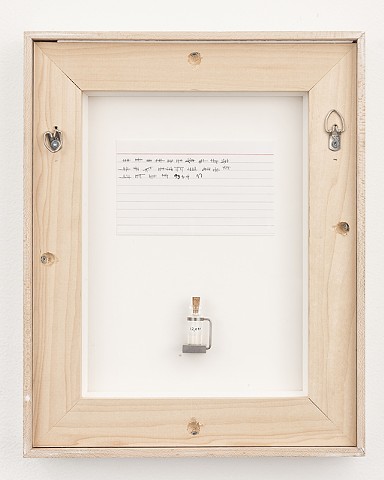

A more specific Andre-inspired piece has Nicol typing an aphorism advocated by Andre on index cards: “If a thing is worth doing once, it’s worth doing again.” Nicol, of course, takes it literally: there are hundreds of these cards here, neatly displayed in a metal drawer, but the project is perpetual.

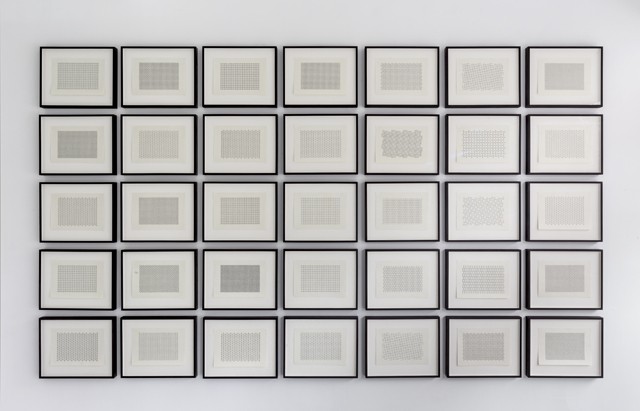

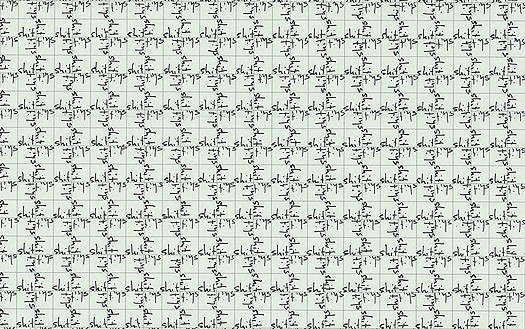

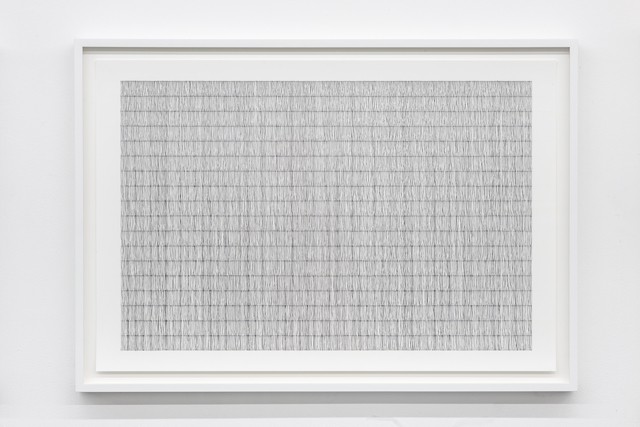

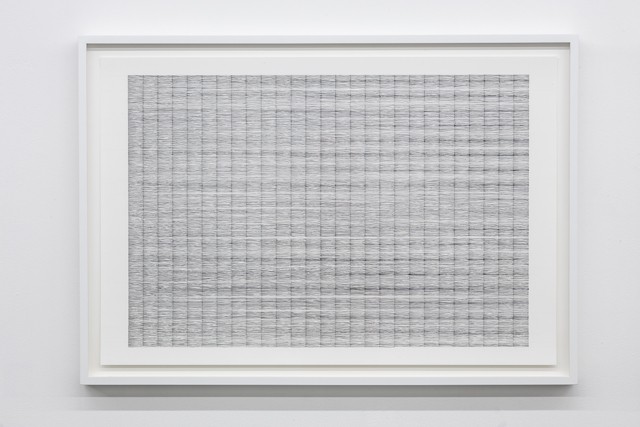

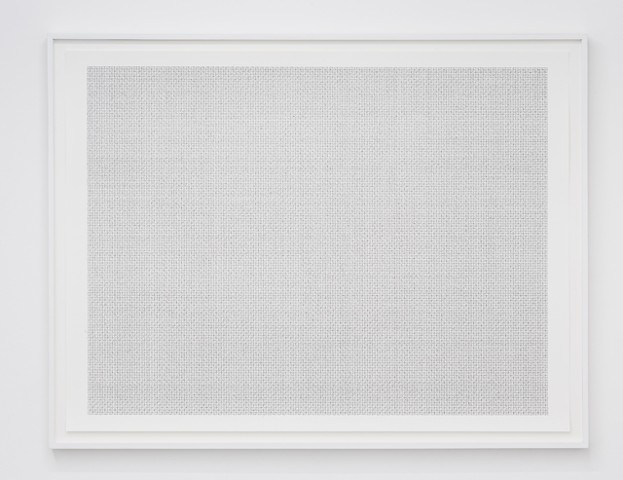

Another influence, informing Nicol’s dark wit, is George Carlin. In the front of the gallery, a grid of 35 works on paper are arrayed five by seven. What’s in them isn’t really for a family newspaper (lest your imagination run wild, they’re tightly clustered, handwritten text), but they’re drawn from Carlin’s famous anti-censorship screed, “Seven words you can never say on television.” Densely repeated here, the comic futility of being muzzled is amplified to high volume and neutered at the same time by the sheer absurdity of it.

At the end of it, Nicol’s overarching project is about time: how it’s used and what we have to show for as it slips away. Nicol, one can safely guess, has mountains: every minute of every day accounted for, ordered, and packed tight.

Time may fly, but Nicol’s account makes us painfully aware, moment by moment, that in some way or form, it all comes home to roost."